Just Dance 202X

Posted: November 22, 2022.

A most personal journey through hemmed in mobility.

By OJ Patterson

Featured Image: Jesse and OJ dancing at Detour SF. Video by Derek Lipkin. Gif by me.

The Saturday April 18, 2020 Super Trashed Just Dance 2020 stream proved strangely popular and uniquely voyeuristic. We gathered to watch a man sweat.

Just Dance is a rhythm/party game series with a very simple goal: move that body (or usually just an arm holding a controller) in an attempt to mirror the choreography of onscreen “coaches” for the highest score. Or, not. The goal can be to jam, rock and roll to a menagerie of bangers and bops.

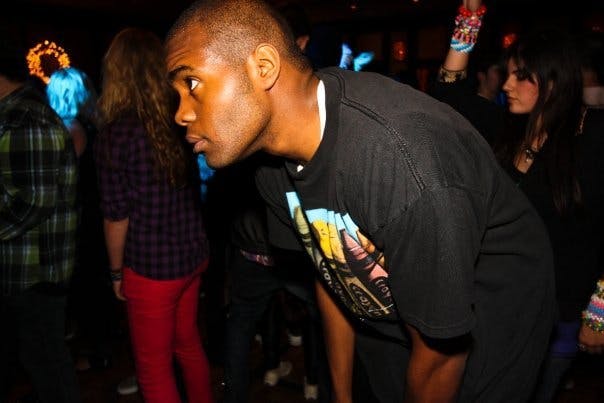

Jesse dancing on stream

Super Trashed’s first Just Dance stream wasn’t our most engaging. Jesse, sporting athletic wear in his living room, was pulled away from responding to the chat for large stretches while he shimmied, twirled, air-humped, and body rolled. In the brief respite between songs, Jesse expressed exhaustion with a shaky charisma.

“Gotta think I’ve been doing this for a couple months straight now [with] how this feels,” Jesse exclaimed. Jesse’s struggle to pronounce the title of Little Big’s esoteric hit “Skibidi” instantly became an all-time channel highlight.

The chatters chimed song suggestions and provided commentary. Some exclaimed they were dancing at home. We couldn’t know how that off-camera, faraway dancing went, if the viewers followed Jesse and Just Dance movements or moved to their own groove. I’d like to imagine a dance party broke out across the internet, across the nation, across the world, spanning time zones, in bedrooms and living rooms and kitchens. However everyone watched or danced along, we knew we were witnessing a random but reassuring rendezvous, communal and invigorating in the ways that listening to music and dancing with others can be, albeit, abstracted and parasocially.

Derek dancing along to Jesse dancing on stream. (Video by Derek Lipkin. Gif by me.)

While the original stream was a trivial attempt to reach a Twitch subscription goal, there was a sequel months later. Together, with viewers’ dollars and Jesse’s aching knees, Super Trashed raised $1,500 over six hours to support organizations fighting against racism and police brutality. At a time when one could only do so much, it was the least we could do.

The history books will say it all, you experienced it for yourself, so I won’t belabor The Thing here. It happened, it’s happening, it will always be happening and it was happening big time in June 2020. That time was arguably the first wave of nostalgia, for March 2020. Gone was the immediate fear of martial law. One person in a household electing to brave the grocery store and then slicking down every item brought in with disinfectant wipes, went from novelty to normalcy. The two boxes of wines for self medication; the hopeful two week, one month, gone-by-Summer timelines; the simplistic epidemiology models of “everybody stand still for two weeks;” and other markers of idyllic folly were adopted, engaged with, entertained, or imagined as everyone learned, relearned, unlearned everything about the world burning outside our windows.

By Summer 2020, as we were finding “solutions” to move forward in place, I struggled to find ways to connect.

I’m a married, childfree, metropolitan Millennial. After a lifetime in the Bay Area, and relocating to Long Beach for my wife Mel’s new job, and then moving to Highland Park in Los Angeles—in married, metropolitan Millennial fashion—to be closer to the social things we enjoy, the options to indulge myself were limitless. As long as I could get home to feed and walk my dog Sandee, any fun and function was attainable. My quarantine was preceded by comedy basketball podcast parties, long walks along the Arroyo Seco, going to the library, going to East LA comedy shows, dreams of going to nearby Dodgers Stadium as a new Los Angeleno, taking the bus, taking the Metro, taking myself out on “artist dates,” being drunk in public, being mindfully reckless, being responsibly mindless.

The greatest casualty for me in “the new normal,” in “these unprecedented times,” was dancing. I was already working remotely and things were busier there than ever. Most of my favorite things found some way to exist online. Basketball players were finishing the season at Disney World. Comedians were coalescing on Zoom. But dancing, even with irregular Treasure Fingers streams and an Apple Music subscription, has never and will never hit the same over the world wide web.

Old Grooves

I love dancing. I’ve loved going out dancing since middle school. School dances were my time to shine. The cafeterias and gymnasiums, or, more specifically, the five foot radius around me, were my stage. I had moves. I had my favorite songs. I often closed my eyes, or opened them only enough to not bump into anybody or anything, and danced wild and loose the entire night, pausing only for slow songs meant for couples (keeping space for Jesus). I ignored or couldn’t see any snickering or gawking from my fellow classmates. The dance floor is where I got free.

Didn’t go to every school social, was never asked to a Sadie Hawkins, wasn’t dancing in the streets or at house parties. But, in the right circumstances, I spun, twirled, juked, bobbed, and let my body loose to anywhere it felt it needed to be (while being careful not to bump into anyone). Dancing on my own, blissed the fuck out.

I dabbled in breakdancing in high school. I ended up going to two proms my senior year: one at my alma mater (where I started as a junior) and one at my former high school (with my friends from K-10)); I was the first on the dance floor at both. By college, I read about and listened to Bloghaus/Electro/Nu disco/French Touch/Baltimore club/Jersey club obsessively, went to desert raves, went to abandoned church raves, went to Otakon convention conference hall raves, went to bars and venues—cordoned off in 18+ areas—to see my favorite DJs, went to concerts, went to festivals, went to church. Always danced as long and as hard as I could any chance I had. After college, returning home without a job or much direction, I found comfort in the belly of Blake’s in Berkeley, Kelly’s Mission Rock in San Francisco, and other EDM haunts.

Rave 2009. Unknown Photographer.

Even as I started stand-up and comedy dominated most of my time and attention, I still found myself flask drinking with strangers in a Tenderloin rave cave, sweaty shuffling at a clandestine party in Golden Gate Park, bouncing around to A-Trak for four hours at Mezzanine, and spontaneously cutting it up with friends as “Move on Up” by Curtis Mayfield hit the jukebox. Iconic club anthems that dominated my rave days, like “Warp 1.9” by the Bloody Beetroots and Steve Aoki and “Barbara Streisand'' by Duck Sauce, can still flash me back to a sweltering night where the details were hazy.

Motown on Mondays at Madrone Art Bar was a perfect mess to get it all out: a place to groove, a place to get fancy, a place to commune with Soul and R&B music inherited from my parents, a place to bring friends, a place to befriend new people, a place too hot, crowded and uncomfortable to dance (but do it anyway). I’ve spent years searching for, navigating to and investing in nights and spots like M.O.M., Sweater Funk, Funky Sole, Funkosphere, Plastic City, The Short Stop, The Knockout, The Echoplex, The Legionnaire Saloon, Make Out Room, Footsies, The Lash. Those vibes, those places, (and the occasional wedding), illuminated where I would dance for the rest of my life. I couldn’t rave forever. But I can always boogie to something timeless.

Day Rave 2010. Photo by Larry Rivera.

And it wasn’t just appreciation for a space to satisfy my specific and personal musical tastes. I grew to love the people there and the people who brought love to the people.

Regulars, like an older woman dripping in glow sticks and breakdancers looking for a way to commandeer a piece of the floor, would nod brief, knowing, silent greetings to each other. Locking eyes with an unknown person when someone else is acting weird, friends dancing goofy to make each other laugh, finding sync and flow in movement of others, with the ethos of the energy, is the truest form of communication.

The DJs there were geniuses. Every night could feature the same songs over the five or so hours but hit different every set. DJs’ creative calculations, techniques, skill, and wisdom offered a new filter to recognize humanity. It was like tuning into someone’s spiritual frequency, being graced with their ideas, their personality. As a distillation of music knowledge, a fraction of innumerable hours poured into consuming LPs, 45s, and CDs, the mix became an entity akin to personhood. There was humor. There was harrow. There was soul.

New Moves

I bought Just Dance 2020 on PlayStation 4, like an idiot. Without a PlayStation Move, Sony’s sleek, “sexy” motion peripheral, I had to use the Just Dance iPhone app to turn my phone into a controller. A few wild swings and a sudden loss of grip sent my phone scattering and shattering. To avoid further damage to my primary phone, I started using an old, spare, seldom-used device from a defunct start-up I used to work for. Similar shattering, similar scattering. A PlayStation camera, purchased to track my movements (and to prevent any further damage), lacked fidelity or ease and only increased my annoyance.

Just Dance 2020 Starting Menu. Photo by me.

The initial impulse when starting to Just Dance is to find familiar songs, search for favorite artists, and select from previews of tracks that jump out while scrolling. “Jesse’s Just Dance Greatest Hits,” highlights from past streams, including “Proud Mary,” “Swish Swish,” and a Swedish boatload of ABBA, was an effective roadmap. No better “strategy guide” than the image of Jesse twirling and whirling and the songs you can associate with it. As I played through the catalog, I noticed the differences between songs scattered across eras in the franchise. There’s a notable advancement from the decade-old series’ humble beginnings, which then had only cover bands and simplistic visuals, to the modern version’s cutscenes, elaborate, environmental storylines, and licensed music. It can be a real trip from track to track.

Everything came to me harder than the floor that cracked my cell phone screens, harder than expected, harder than I’d like. Learning how to Just Dance, how to read the pictographs that foreshadowed steps and calculating controller sensitivity, had a steep curve. “Failing” at a party game felt unacceptable. Even as the pretentious, nonplussed intellectual I fashion myself to be, I became frustrated. Miffed by my low scores, my myopic, perfectionist, obsessive, and competitive spirit towards trivial things flared uncomfortably and uncontrollably. I was also woefully unfamiliar with, if not actively resistant to, the game’s modern Pop music stylings.

The price point built resolve. $40 for the game and $10 for three months of Unlimited weren’t going to go unused like Daily Burn and Headspace subscriptions in the past. I got better and grew to enjoy music I would have never searched for or heard of outside of the game. “7 Rings” by Ariana Grande, a cool and sleek sonic atmosphere, is enriched with verve and catharsis via the game's engagement and interpretation. “Bad Boy” by Riton & Kah-Lo is a loopy, swishy, sugary, frozen Daiquiri of a jam. “Old Town Road (Remix)” grew on me. “Baby Shark” is cute. The game’s choreography emerged as an effervescent feedback loop, progressively emergent on replay, as I began to remember certain moves and sequences. And, hey. All of my Just Dance growing pains were better than the alternatives.

Pandemic protocol became a personal choice and private practice. Mel and I were extra cautious. As if remaining indoors would make everything go back to normal quicker, we stayed inside and limited exposure as much as we could. My walking routes were suddenly filled with people who couldn’t go to their gym. Video chat comedy shows, could feel like a hostage situation, could become indecipherable with technical errors. Powerless and agitated, the anger and frustration bled towards all the “selfish” people who chose their own pleasure and release, who kept everyone else quarantined by being outside. Couldn’t trust anyone—family, friends, or would-be fellow revelers—who traveled freely and had nights on the town while I marked passing days with tallies on the wall. Couldn’t like or sympathize with how they were “dealing.”

Land of 1000 Dances

Dripping in sweat, drowning in memories, a wave of deja vu shivered down my spine. I had spent prior summers slightly frustrated in the passionate pursuit of feverish frivolity, an adolescent, embarrassing struggle to conquer Dance Dance Revolution. DDR, a classic rhythm video game and arcade series, was a source of social currency and shared language. My friends and I obsessed over the step charts printed from DDRFreakdotCom. Buses and BART to Golf n Games in Antioch or QZar and Mountain Mike’s in Concord, loitering at the machines for hours, stretched out our allowances in 50¢ increments. Thin vinyl dance pad controllers duct taped to the carpet in my childhood bedroom floor struggled to remain in one place. To focus on being either a proficiency-minded technical player or interpretive “freestyle'' player was a big decision. Songs like “Kind Lady,” “I believe in Miracles,'' and “PUT YOUR FAITH IN ME,” sung in high school hallways and at birthday parties, are landmarks, totems and needle drops on my salad days’ soundtrack.

Spinning at college DJ club.

Dancing in college quad during DJ club meeting.

And even before Dance Dance Revolution, Bust-A-Groove, a hybrid music/fighting PlayStation game, literally taught me how to dance. The game, arguably the nerdiest controller-based version of You Got Served, came with a “Dance View,” allowing players to view characters perform dance moves over and over. As a pre-YouTube latchkey kid, I found a fascination and utility in watching and mimicking those chunky-3D avatars.

The left-right-left-right of “El Ritmo Tropical” lives in my bones; the chorus to “Shorty and the E-Z Mouse” lives in my heart. But I would lose interest in the rhythm game genre after high school. College was the last gasp. My roommate’s metal dance pad and DDR PC mod StepMania—epitome of the foot-based dance game genre due to a nearly unlimited and customizable amount of songs—was the last place for stomping left, right, up, down before embarking to clubs, backyards and parks.

Humors

On the Nintendo Switch, with the console’s built-in motion controller and strap, Just Dance 2021 officially reignited a passion for moving to music corresponding to video game prompts. I watched trailers, sought out song announcements, pre-ordered the game; it felt like being a kid again. The Just Dance 2021 track list is bonkers and the accompanying visuals are beautifully inventive. Inclusion of songs like “Feel Special” by TWICE and “Ice Cream” by BLACKPINK, while not quite as high on the banger-meter as Just Dance 2020’s “Fancy” or “Kill This Noise,” gave Just Dance 2021 the feeling of a “true sequel.”

It took me a few months and two different iterations of the franchise, but dripping in sweat, giddy with giggles I finally and fully understand how funny Just Dance is.

Most of the series’ background scenarios and enveloping environments span from “glorified screensaver,” as seen in “Kick It," to “artificial arena concert stage,” as with “Alexandrie Alexandra," to “thematic, overwrought abstraction (that’s too weird for my blood),” like the technosexual-nightmare exploding out of “Lacrimosa," to “thematic, overwrought abstraction (that appeals to my personal sensibilities),” like the lush, lucha “Que Tire Pa Lante."

Separately, there are songs and scenes with intentionally funny flourishes, where kitsch, camp, or wordplay manifests literally. Someone in an anthropomorphic panda or moose suit dancing to, well, anything, is a series calling card. Silly premises, like a skinny coach in a loose tank top flexing to “I’m Sexy And I Know It” or old men ambling around to “Don’t Worry Be Happy,” have their charm. Punctuating with a punchline, an avatar can fall out of a fantasy (“Fancy Footwork”), or depart dismembered (“Monster Mash”), or kiss as stiff as plastic (“Barbie Girl”).

In Just Dance 2021 itself, “Juice (Alternate)” has players swing hips with dizzy-eyed smoothies. “Joone Khodet,” where two bellhops skip and slide in front of magical elevator portals, is boundless with cute, fantastical juxtaposition. Juvenile, hand-drawn hijinks escalate hysterically in “Uno.”

The game’s unique and rich personality, oozing through its multinational, multicultural milieu, plugs a Matrix-style AUX cord into the pleasure centers of my brain. There’s no more efficient shot of serotonin than pantomiming “Kulikitaka” cat’s wiggles and paw waves. “The Get Down” is a technicolor journey to the center of the Earth complete with lip-syncing fossils and party-rocking aliens. “You’re the First, the Last, My Everything,” which starts, hilariously, with a bunch of coaches entering an elevator, unconsciously stuck in an atmosphere of toxic masculinity and corporate stodginess, slowly busting out in a series of waddles and arm flaps that brings hope for a brand new day.

There’s an elevating effect playing Just Dance, where players reach a synergy with the game, a flow akin to intuiting the right sequence of light and heavy jumps in Super Mario or feeling through the eye of a scrolling shooter bullet hell hurricane. It’s a bodily awareness without judgment and perception without cynicism. Am I really “chicken legging” across my living room? Did my mouse avatar just break out of prison? Yup! As a grown-up, it’s depressingly uncommon to revel in pure, unironic ridiculousness. With Just Dance everything is encouraged, anything is permitted, and nothing is obligated. The wry, quirky, colorful, saccharine whimsy, which utilizes comedy as a grand diffuser and laughter as a universal language, feels representative of the game’s internationally diverse developers at Ubisoft Paris, Ubisoft Milan, Ubisoft Montreal, Ubisoft Elsewhere.

New Face: Developers of Just Dance swapped in for Psy’s titular new faces.

It’s like when, as the Oscars are fast approaching, you find a theater screening all the Academy Award nominated animated shorts. And there, while you’re enjoying all of them, you notice that one in particular has no dialog or the character design exaggerates human anatomy in an unfamiliar way. And at that moment, instead of resisting an inherent, inherited incongruity, instead of thinking “what the hell, this doesn’t look like Garfield and Friends,” or whatever codified art style you’re accustomed to, you settle into the act of “being open minded.” This commitment to “evolving past” your “ingrained reactionary ignorance” helps foster appreciation for noted cultural differences. Then, like an astral projection, you can fully see what resonates with you from a consented curiosity; you have gratitude for the world’s vast and various expressions life can create. Oh, and then a character in that foreign animated short falls over and you laugh. That’s Just Dance.

The only drawback is, despite the Ubisoft Connect feature keeping track of my name and purchases, my playlists didn’t transfer to Just Dance 2021 (nor will they transfer to Just Dance 2022). Meticulously scrolling through Just Dance Unlimited, reconfirming my affinity for certain songs or leaving said songs in the endless pit of hits, remaking my high-cardio and Halloween collections, is an archaic and tedious ritual reminiscent of modifying rosters for sports video games before consoles could connect to the Internet.

Co-Op

Increased aptitude bolstered my attitude. I felt better as I did better; I did better as I played more. I also gained more: an fresh and precious thread of cohesiveness. Just Dance became the glue holding together the new world.

Saturdays were reserved for afternoon boogie dates. Mel made her own playlists. Just Dance became interwoven in our relationship’s lexicon. “I’m a tomato,” referring to the alternate stage for Jamaroquai’s “Automaton,” or echoing “Speeder-Man,” affecting the specifically French-language-lacquered pronunciation of “Spider-Man” in “Le Bal Masque,” were more than inside jokes. The game’s kinetic verbiage, physical associations to words, songs, culture, and ideas, was an expansion pack, a new accent, a new slang for Mel and I.

The movies, television, and music people bring into their romantic relationships, the pop culture formative to their individual cores, can sometimes grow into a shared affinity. “What’s that?” or “Never in my life did I think I would watch [blank]” can turn into an empathetic “this song helps me understand you so much better” or a surprising “Clerks is great!” Similarly, finding out the intersection of loves is fun. “Oh, you like Gorillaz too?” or “I saw your Tumblr post. May (2005) is a great movie,” have their own stickiness.

The new shit from newfound media, first watches/listens while cuddled up, like landmarks in the grand greenery of Sense and Sensibility (1995), or sharing an sudden obsession with the oddball band Sparks, is just as important, especially in a pandemic.

New experiences, like our commitment to Just Dance, mutually mysterious, tactile, rich, ripe with unexpected delights while encircled by the world’s miserable unknowables, added depth to a noble distraction. The “silly party game exercise realm” that gave us something to look forward to where there wasn’t much on the horizon, became something to look forward to together that felt fundamentally different from any other form of communion, which provided added relief.

The lockdown tore down or reinforced many of our friends’ relationships: a spark to change or inspiration to double down. It feels garish to say but Mel and I didn’t just grow closer, it felt like we thrived. A lot of that resilience was solidified way before being shutdown could test it. Still, side-by-side, swaying and waving in harmony, Just Dancing allowed us to say without speaking, “I’m glad I like the person I’m quarantining with. I’m glad we worked so hard, from years ago to today, to work out. This is a lot of fun and I’m glad to share it with you. I love you.”

Before the pandemic, before being married, before moving “down South” the I-5 from San Francisco, before I met Mel, I lived in a converted dining room. The house had a rotating roster of double-digit roommates. So many dudes, so many dishes. And I was content. I can only imagine where that version of me would be now if things were different, how I would navigate quarantine in that environment, if I would have even remained in that house up to 2020.

The vaccine rollout came with the hope of people having a ball in the streets by Fall. The Roaring 20s (Part 2) was off to a rocky start, but we’d get it right. Second dose kicked my ass; someone in our Super Trashed Discord had the clutch advice for medicinal Gatorade. Parties, flights, and family reunions, the things that would be worth all the solitude, sadness, and body aches, felt just around the corner. In the meantime, first, awkward meetings with old friends, where vaccination cards rested in wallets and fanny packs, where we wore face masks outside, would have to do. The park and day our friends picked for a picnic unwittingly coincided with the site and time of a rally to combat anti-Asian hate crimes in San Gabriel Valley. Fliers, QR codes, donations—our brief excursion into the Outside World reminded us that it was still on fire.

Pop Crisis

Just Dance 2022 is more of the same, which is great. Great game, great songs, and great times. “You Can Dance” by Chilly Gonzales, annoyingly enveloped in trivial “1980s aerobics” histrionics, is such a nu disco cult classic, so evocative of my blog/rave young adulthood, so incredibly “my shit,” that I couldn’t believe it’s officially a part of the Just Dance canon. “Girl Like Me” by Shakira and The Black Eyed Peas is a breathtaking mix of minimalist, surreal landscapes, abstract, geometrical architecture and “The Invisible Man“ (1933) realness. “Levitating”… Interesting thing about “Levitating.”

Switch wristband motion controller, perfect for Just Dance. Gifted by Super Trashed Secret Santa (Derek). Photo by me.

From the immediate, interconnected, inimitable Super Trashed universe, where friends of friends and far off acquaintances of our collective can become favorite Twitter follows and parasocial tastemakers, I had been hipped to Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgic (an 11-song, 37-minute Pop masterpiece) relatively early. The album’s first and title track, robust and robotic, immediately sets a moody, smartass mood. “Love Again,” “Cool,” “Good in Bed,” and “Hallucinate” shift through all the romances and romanticism found in dark, neon-tinged nights. The shift in syrupy groove from verse to chorus in “Pretty Please” feels like a rollercoaster dip. Middle eights found in “Levitating” and “Physical” could rival the Golden Gate and George Washington as “iconic bridges.”

It was one of the rare times in my music fandom that I was slightly ahead of the curve to a huge rise in an artist’s career. Like, I couldn’t “take credit” for listening to Dua Lipa’s refreshing dissertation on disco that much sooner than “Levitating” becoming “the official song” of the NBA playoffs. And she had appeared in Just Dance with “Don’t Stop Now” (JD 2020) and “One Kiss” (JD 2019). Nevertheless, it still felt good to have a slightly better awareness to recognize her growing eminence.

Dripping in sweat, welling with emotion, Just Dance 2021 songs like “Boombayah,” “good 4 u,” and “Judas” triggered an internal reaction bordering on “existential crisis.” How is this music so good? What is it stirring in me? When did I go away from this? Where was I led astray? Why had everything I enjoyed, from this one particular genre, mostly from artists who happen to be of a marginalized gender, get filtered through the most roundabout, assigned, subverted, borderline insincere lens possible?

I scanned my dial, my highest and lowest stations, measured my memories, reconstructed my past and hypothesized. An Einstein–Rosen bridge, a 2001: A Space Odyssey color tunnel, an MCU threaded-rope of a multiverse, Plato’s cave, a ray model of a dark, cramped silo turning a single beam into a million points of light, Double Consciousness, feminist frequencies, tessellations of intersectionality including race, sex, gender, class, creed, and character—the science of Pop dysmorphia wasn’t exact and a representative model doesn’t exist.

The first two albums I’ve personally owned were Spice and Spiceworld, Christmas gifts. (They were probably purchased upon my request with raised eyebrows). The Spice Girls weren’t even “Pop music” to me. I didn’t know that term or what it meant. Scary, Sporty, Baby, Ginger, and Posh were no different than Power Rangers or Ninja Turtles to me: a cultural phenomenon featuring a cadre of fun, distinct characters with special signifiers and code names. Spice Girls’ superpowers just happened to be singing and choreography. I played their music ad nauseam. I love their movie. I love their music videos. “Say You’ll Be There,” is top-three all time. I even tried to love the Ginger-less “Holler.” (It’s okay).

The Spice Girls’ breakup marked a slow disenchantment. At that point, in 1998, I had firm and contradicting JaRules about music. Things could be “for girls” but not too much. And if too many girls liked a thing, chuck it in the bin. Boy bands were hit or miss. N’Sync, yes, Backstreet Boys, not the “mushy stuff,“ 98 Degrees, absolutely not. Woman icons—your Britneys, Christinas, Jessicas, Mandys—were nice but risked feeling too frivolous. If rock was too pop, meaning that the girls in my class wore the band’s merch, I would reject it with righteous indignation. If rap was too pop, it wasn’t “real” rap. And don’t even get the child-me started about Celine Dion, or any reference to Titanic (a movie child-me would never seen), because of a lizard-brain jealousy of Jack. You see the pattern?

By middle school, after succumbing to peer pressure—or, my presumption of the requirements my peers “demanded” of me—my heart hardened. I discarded my curiosity. My friends, foes, television, radio and any source of validation through social programming determined my cultural trajectory. At some point I was a backward red fitted New Era hat away from going full nu metal and a black leather jacket away from being a Post-punk revivalist. Backpack rap, electro, rock, and whatever Live 105 told me was “alternative” enough to be “good music” were entirely too important materials to my pretentious facade of an identity. The way “Pop music” didn’t just mean “popular” but also codified to being “corporate and vapid” was a fool's distinction. Buying into the myth of “popular music” also conveniently ignored the inverse marketing to make people feel unique (and isolated) for liking outsider music, cult bands and massively popular “antisocial” acts. Artists I formed a personality around were often signed to the same major labels of Pop artists I lamented about, just under a cooler, more “legitimate” imprint. The tiniest quirk or charm (that spoke to me specifically) meant “artistic integrity.” But, you know what? I like a good hook. I love a memorable pre-chorus. A rising, stirring melody giving way to a sing-a-long worthy chorus? Yes! A million times yes!

Any interest in a woman-identifying creative force was almost always initially adopted as lark. Rilo Kiley (and later Jenny Lewis and the Watson Twins (and then just Jenny Lewis)), who became de facto avatars for a maturing angst, were sought out initially because I heard that “the girl from Troop Beverly Hills and The Wizard was in a band. Big Boi and P Diddy co-signed Janelle Monae before I decided to tap into the enriching, revolutionary and fully-rendered worldbuilding evident in all her work. Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill, Missy Elliott, Kelis, Feist, St. Vincent, M.I.A., Rye Rye, Uffie, Maria Rita, Natalie Lafourcade, Solange, Robyn, Kimbra and definitionally-not-man-identifying or not-fully-man-identifying bands like The Blow, The Bird and the Bee, CSS, and Le Tigre were all compartmentalized into more palatable genres of music than “Pop.” No, I was listening to neo-soul, hip-hop, MPB, electroclash, synth, rock, folk, indie, R&B, dance, dance-punk, World, electronic, art rock. “There’s a difference.”

My fandom couldn’t just be an appreciation of their power, a resonance with their underdog, independent, indomitable persistence to be soft, strong, cautious, full-bodied and emotionally intelligent while dismissed and scrutinized on a molecular level for every little thing. I couldn’t just relate, couldn’t only aspire to be what those women inspired in me without irony, without an external, extraneous permission. Because “that” is “them,” they are beautiful, beauty is embarrassing, and any failure to adopt or live up to that beauty would be unbearable.

It could have been my loneliness killing me. Giving space for self compassion and grace, Pop music fandom can feel like being surrounded by water, on an island. There’s plenty of room and ample opportunity to adorn the terrain with jewel cases, ticket stubs, posters and other artifacts. Zoom out a little and you can see your archipelago, activity on other islands, a friend’s tweet or a Spotify feed of shared songs and artists you’d consider “guilty pleasures,” that they consider “Tuesday Moods.” Zoom out further and you can see the mainland and know there are certain music truths that are hella basic: the Beatles are good, Tina Turner is underrated, showtunes are catchy. Zoom all the way out and you can see everything: the peninsulas, the straits, the channels, the ports, the business, the culture, who Pop is “for,” and who makes the genre their own.

When the tide is low, an isthmus can appear, allowing you to cautiously navigate to those other lands, to hike across another person’s or group’s preferred soundscape, noting similarities and disharmony to your own plot of Pop culture. The tide eventually turns, the water rises, calling you back to your playlists and mixtapes, lest you lose your own discernment and leave someone else to determine your desire forever. You scamper back to the confectionary sounds that you cherish the most with new awareness of a disparate genre or a new tune to gush over.

Back on your island, eyeing the horizon, you noticed some people aren’t stuck to their landmass. They’re on boats. Whether partying on a yacht, or rowing by themselves, these select, ultra cool, confident people are free to go anywhere any time they please. And they look like they’re having a ball. Pop music for these people isn’t just a moment, it’s movements. It’s not just something to hold dear or navigate; Pop music is a thing to “know,” to live in, to converse with, to manipulate. They have community and language. They are in formation. They feel like a natural… (however they identify). They’re not excluding you personally, but they’re an exclusive collection. You can only curiously observe them from your shore with the sand in your toes. So sad, too bad.

Trying desperately to keep up with Ciara’s “Level Up” is harder than it should be. Recognizing my past and ingrained misogyny carries a notable tension, like wrist weights or running with a deployed parachute, carries a notable tension. The resulting joy is worth the momentary discomfort, and pushing through to accept good music for what it is is relatively easy. But still, the fact that there’s even extra effort to acknowledge and accommodate a fuller self, is disconcerting. Who did my unchecked, unconscious, unfiltered bias and prejudiced social conditioning serve? Not me. Not my cultural literacy or comfort in my own skin. Even now I have to notice immediately, isolate and hold any instinctual denial in indulgence to the light, to see what fears and discomfort are bubbling to the surface.

It’s tragic. I used to blast Kylie Minogue with unabashed carefreedom. Now I can only try to peer back to see all that I’ve missed.

That’s a cool thing about Just Dance. Even at its most surface level, even as an incomplete or warped perspective of modern music, even if prioritizing “what artist allowed usage of” or “what people want to dance to,” and not “artist’s best or most popular song,” each subsequent edition is a new playlist that says something about the state of Pop music. Since I mostly haven’t heard the collected tracks before, especially not since embracing my newfound resolve, Just Dance innately germinates further discovery. Hopefully whatever discomfort I’ve grown to associate with Pop music will wane with exposure and persistence. Far be it from me to dismiss music’s healing properties. Can’t rule out an honest investment into Meghan Trainor, Katy Perry, or Charli XCX as the final frontier for enlightenment. Not in this day and age. Am I a Beyonce concert away from rooting out a fear I fear will never go away? Stranger things have happened.

Smalltown Boy

Mel likes to imagine that Just Dance is a boon for LGBTQ+ youth, that the series’ art direction and songlist is a safe place to explore attraction, aesthetic, and allowance. It's a pretty apt and accurate assertion. Just Dance is rife with codified signifiers, a representative roster. Anthems like “Nails, Hair, Hips, Heels” by Todrick Hall (JD 2022), “Boy, You Can Keep It” by Alex Newell (JD 2021), “Born This Way” by Lady Gaga (JD 2016), “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” by Sylvester (JD 2022) to name a few, makes Just Dance one of the few mainstream games that curates, caters and pays homage to LGBTQ+ artists without any asterisks or apology. It’s not perfect but it’s purposeful.

And it makes sense. Art, entertainment, culture, and especially “dance” as an expression, discipline, and lifestyle, has been a haven for a lot of marginalized people. Courageously, for their own joy and survival, those people create their own spaces, music, looks, movement, which, inevitably, can get torn down by the virulently homophobic establishment or co-opted into the mainstream without due credit or appreciation. It’s gotten better, it’s getting better. Art is art, dope is dope, love is love, and, excuse the cynicism, money talks. Still, one can only wonder how newer generations experience emerging confluences in culture. Is it like hip-hop, that went from fad to form, joke to serious business, misunderstood to undeniable, over a 50 year span? Or is it something else, something that’s out in the open but not fully embraced? Do LGBTQ+ children hide away what could be construed as “this or that,” by “them and those” until they're able to openly embrace their totality with dignity and pride?

Is it that simple? Did my wholesale abandonment of Pop as a teenager, forsaking a frivolous side deemed dangerously superfluous, come from base, crude homophobia? Heartbreaking.

Growing up, growing tall, I grew self conscious as I grew more aware, actively shirking any femininity that’d be doubly worse to embody as a straight, good, Christian kid. My posture changed. My gestures took form, took pause, then shifted. I wasn’t being “careful,” but I was cautious. Not that there could be any harm beyond eternal discomfort, external disappointment, or expedited disillusionment with my upbring. Shamefully, as a tween-to-teenager in the early aughts, I just didn’t want to be seen as even potentially “that way,” so things in that direction weren’t considered, examined or inhabited. All questioning led to the same answer, “no.” Inquisition stifled in the larynx. Ideation snuffed immediately from thought.

Sometime, between Just Dance 2020 and 2022, a sense memory occurred, like an unexpected pang of lighting across a cloudless day, that broke my heart. I remembered that I had encountered the franchise much before my quarantine-inspired entanglement.

The Michael Jackson Experience, an early Just Dance artist-themed spinoff, had just come out. The ubiquity of Michael Jackson and the omnipresence of the Nintendo Wii was a potent combination. Everyone at a mixed-age get together, composed of everyone from infants to kids to grown folks to elders, loved swinging themselves wildly to the world’s catchiest songs according to visual and choreography recreations of the most all-time iconic music videos. The terms “family fun” and “casual” couldn’t be more evident in a room unless it was a commercial for Scandia or The Exploratorium.

One boy, no older than eight or nine, wasn’t having it. One of the game’s selections, maybe “Dirty Diana” or “Remember the Time”, featured both a man- and woman-presenting coach. No clue if players could select the same coach in those days, able to perform the same moves in parallel tandem. But, according to this child, since “the boy” was already chosen by another boy, he was being asked to pick “the girl.” The unselected youth became loud, upset, inconsolable as the adults converged. He still wanted to play, he just didn’t want to be “the girl.” Whether because the other child wouldn’t budge from selecting the “boy” avatar, or because of his increasingly wrought yet innately incommunicable emotions, or because he simply wasn’t getting his way, or because he was embarrassed by the growing, unwanted attention, with tears streaming down his face, the boy slammed his controller down. He was whisked away in awkward silence (you know, besides the repeating Michael Jackson chorus playing during the idling game’s menu). “The Way You Make Me Feel….”

Everyone should be who they are, who they want to be. Gender and identity are hard to actualize for adults, let alone for children. People should be able to present and embody whatever avatar they want, in the digital or material world. But, from what I could remember, this felt different. It didn’t feel like owning masculinity; it felt like fighting femininity. Fear. It felt as if the boy had already metabolized toxic masculinity into a fiery rejection of hypothetical femininity. His meltdown at even entertaining the benign notion of playing a “girl character” haunts.

Can’t say confidently, if I was that little boy, that things would be different, that I would be courageous and true about what I once loved and recently rekindled a passion for. I’m powered by a spirit and glory of 90s’ Pop machine reminisced, rediscovered, and reimagined through modern Pop machinations. The cynical social atmosphere of my adolescence and teen years was someone’s early childhood. If I was born a decade later, into the late 90s and maturing in the 00s, I’d probably succumb to the Millennium’s chilling cool.

Even not, if I acquiesced to my impulses and intrigue towards the Just Dance experience as that naught-era child, there may not be wholehearted, wondrous acceptance; youthful caveats towards “boy” songs and ironic softness probably remain. What age would Just Dance have been “fun?” At what age it would have been “bold?” When would it be “brave,” and at which age it would have become liberating?

The critical path to where I am, where I’m going, has so many on ramps and offshoots. Baffling to think that something so emergently instrumental as Just Dance wouldn’t be viable under certain conditions. Impossible to know, unpleasant to reconcile. Hell, it took the pandemic and a boatload of therapy to even get here.

Outbroken

I’m sorry. Please excuse me and this navel gazing, tired rumination. Apologies further for this indulgent “breaking the fourth wall” contrivance. In conception, I imagined less to say, less to express than that I really like a video game. “Fun, party game is fun,” “a cool way to work out,” “oddly evocative of rhythm games past” or something to that effect was all I thought I needed. Instead, this is going on and on and on. Even now. On and on. Half way through, I recognized a sad irony. It’s like a television show about trauma and mental health, where, because of the cyclically resetting nature of television, nothing can “fix” the sad, anthropomorphic horse or the gangster having panic attacks. Despite many attempts for that character to find a solution, the many pop psychology theories and trends presented, the show becomes the embodiment of that character’s inability to transcend their diagnosis, the show becomes depression or anxiety. This piece about the pandemic is now the pandemic: bloated, meandering, listless, wistful, seemingly endless. I find myself regretfully returning to it over months, frustrated it’s not over and that I can’t move on. Similarly, Just Dance has taken on elements of sheltering in place: a rich inner world, shuttered away, with an expiration date on new delights. Maybe that’s the thing. Everything looks different after March 2020. The Pandemic is a process, a paradigm, a filter, a kaleidoscope. And I’m just… so… tired.

The New Normal seems eerily like the old. All the social gatherings slowly reemerged. And the qualifiers to experience them quickly evaporated. No more outside shows and dance parties in the park. Once inside, after a few months, precautions mostly subsided, perceptions skewed. Every comedy show remains a volley of particles and droplets between act and audience, mask optional. Every dance floor, with naked faces huffing and puffing raw respiration, at condensed, divey venues with lax vax requirements, sounds like a bad idea, all things considered, and yet. Precursory audits on elective engagements, examining personal thresholds, holding desire to scrutiny, can be laborious enough to not go through most doors.

So much of the COVID-19 era has been about building walls, barriers, between thoughts, behaviors, to separate people and separate from people. People now have to navigate the resulting maze. The path gets equally simpler and more complex if you or someone else bust down those walls with a sledgehammer; grinning faces emerging from the new holes express one part uneasy relief and one part “uh, nice hole but what are we gonna do about all this dust and rubble?”

Some events are regular or popular enough to maintain themselves in my absence, available to meet again on the other side of the current cause for pause and discomfort. Other evenings I wouldn’t miss for the world.

Two years and change after the before times, I’m at a beautiful wedding. Vaccination, a small price for a joyous time, was paid three times over. It’s surprisingly easy to recognize punims from a past life, from a forsaken world, even the few behind face masks. (A small but mighty “covered kinship” validates also wearing a mask. Wonder where the others have theirs: in their pockets, their cars, in their hotel, at home, on the floor, in the trash, on a pyre, in the dirt?)

Weddings are extremely “my shit.” Celebrating friends’ bonds (with giving gifts, taking photos, and boogying for hours) are what dreams are made of. Giggin in unexpected synergy with a relative or relative stranger, who you’re confident has a shared admiration for (at least two) people you care about? Fuck yeah. Gabbing and pontification about the nature of connection? Sign me up. Screaming your name and how you know the newlyweds to someone over impossibly loud Nelly or Pitbull? What a wonderful world.

I’ve received the most compliments about how I get down from people a little lit up by the cocktail hour. Outside the realm of a reception, such attention makes my skin crawl. Most dancers express praise and gratitude to each other in glances, head nods, mimicry, or, at most, chanting “aye aye aye” during a circle or Soul Train line.

“You’re such a good dancer.” Shudder. In those moments, even with the kindest words and pure intent, usually by someone who I haven’t seen sharing the dance floor, my bubble has been pierced. I’ve been unquestionably, untowardly perceived. The courteous, strained “thank you” in response always multiplies any angst or sense of betrayal, resentment that my place to unwind and unmind is now a stage, like I’m busking for praise.

It doesn’t happen often, God bless. I’ve conditioned myself to “move it, move it” past the discomfort quickly, though undoubtedly unnerved and less expressive in the interaction’s radioactive afterglow.

Those intrusions tend to not bother as much at a wedding. Any inherent or inferred awkwardness in those exchanges is washed away by raw, uncut happiness from a great time with loved ones.

So many people I know got engaged shortly before or during the COVID-19 outbreak. Their ceremony dates moved up and moved back, the guestlist scaled down or abandoned, clawing to get through a small window of opportunity or a fog of uncertainty.

At this vaccinated wedding, most of me can appreciate the reconnection, the camaraderie, the small, special moments that make mountainous memories. But also, a not-so-insignificant part of me was processing dread, stress, future tests and any life interruptions a future diagnosis can determine. “A roll of the dice,” fails to accurately capture the cost-benefit analysis every modern get together requires. At least if you’re gambling money there’s a chance to win. Every (potential) extracurricular exposure is all about losing as little as possible. Mark three-to-five days from the event on your calendar. Monitor every sniff or cough around you during and with yourself afterwards. Hope for the best.

Worst part isn’t the ball of nerves, conflicted smiles and stark reality that our government royally failed us. The real distress is the allure, the thrall, the intoxication. And I’m not talking about the His and Hers cocktails. Once there’s one slip in protocol—pulling down your mask to be heard over music, pocketing your protection to snack on hors d’oeuvres, sharing a hearty laugh in the outdoor lounge—it’s nearly impossible to not be caught up in (and give into) the ultimate acquiescence.

The DJ played a banger and the bandwagon effect kicked in hard; dancing at a party without a mask, without a care in the world, “feels right, feels normal.” The moment invited thinking, “I could get used to this.” Which is how we got into this situation in the first place, right? Too many defaulting to their base, natural urges, to do what they want, to be what they think they need to be? Swept up, you can’t help but wonder who got this “right.” Videos of people in packed swimming pools and concerts at the height of the pandemic were seared in your mind as the height of selfishness. Even after rounds of vaccinations, the principle is the same. Who checked vax cards, who scanned QR codes, who confirmed or enforced the state guidelines at this ceremony? Exactly. Does it even matter? Did it ever? Still, at the moment, I’m here, 1 million Americans aren’t. It’s an ongoing tragedy. But I’m alive.

heading to the dance floor when the wedding DJ plays “Mr. Brightside” pic.twitter.com/JlIub14h6A

— shamus (@shamus_clancy) October 16, 2022

A glass shattered in the middle of a dense dance floor during “Mr. Brightside.” Worry of slipping and falling with slightly older, creaky, out-of-practice bones is the sobering indication to quit while ahead. Mel and I went to the hotel, went back home, and waited.

“I miss dancing with you,” Mel expressed. I agreed. In the aforementioned wedding evenings and bar nights, sweat and movement rumping clothes and adrenaline twinkling in eyes, Mel could be found as well.

While not the same blissed-out, shut-eye blitz as dancing alone, grooving in tune with Mel and our collective rhythm, has been a staple holding us together since the beginning. We’ve braved winding, middle of nowhere roads to “big days” across the country and early vax-era concerts to ultimately reach the dance floor, to reach each other. Prancing and romancing, communicating only with smiles and smize, was always a crystallizing highlight in our adventures.

First Dance: Mel and I at Our Wedding. Photo by Charles Patterson, my father.

First Dance: Mel and I at Our Wedding. Photo by Charles Patterson, my father.

Our own wedding, a semi-sarcastic winter wonderland that projected unconventional Christmas scenes from TV/movies and gave out cookie cutters as party favors, started with a first dance to “Last Dance” by Donna Summer and ended with Mel, after a costume change, twirling unbridled on the floor of the Women’s Club of Orange.

I’ll always delight at how Mel gyrates and pumps with unpredictable meters and irrepressible form. Observing and engaging with her, with us, with that, in the nightlife microcosms of twilight and vibration, is another thing taken by “these days,” another thing I’m unsure we’ll get fully back.

Hereafter

There’s no fixing it. No way to reclaim what was lost. To embrace what’s different is to ignore the unrecognizable. I’m not comfortable going gung ho, to push past good sense and bad vibes in order to stake claim to what once gave my life volume, definition, relief and purpose. It wouldn’t feel the same. Even with the same attributes and parameters, a critical caveat must be accounted for, and thus diminishes the endeavor? Redefining “purpose” in the midst of a global catastrophe seems ghoulishly privileged, but here we are.

When changing directions if a path is blocked, a road’s too rocky, a disconnect is too glaring, malleability is a virtue, to a point. I take pride in being able to push through with what matters and removing what doesn’t serve me. There’s no bullshit I’m resigned to suffer or retain as a condition for living. Still, how many pivots until one finds themselves cornered? Every burned bridge, every tie severed, every examination, deconstruction and overhaul, no matter how much in the name of care, protection, and self sufficiency, is one less place to know, one more time (or person, or group, or investment) to mourn. As whole, safe and fulfilled as one can be, there’s a risk of feeling siloed in a fortress of solitude.

Sometimes you get bored of feeling so fucking alone. Not tired, exhausted, or overwhelmed. The loneliness is too comfortable as if to alchemize armor into skin. Turning from “I’m lonely” to “I’m loneliness” leaves holes in hearts, lumps in throats, clutching at oneself for relief. God, I need to go outside. What’s that? Another variant? People are arguing about vaccines? And the CDC just tweeted a shrugging emoji? I guess I’ll stay inside. I guess I’ll Just Dance.

Of the many things I’ve been forced to consider, remember, attempt, fail, understand, accept and acknowledge in the last few years, I do know this: I don’t always like dancing.

My mom’s wedding had a popping dance floor; my teenage self sulked on the side in protest. When people ask or tell me to dance, when forced, I’m glued to my seat in resentment. I couldn’t muster movement (or standing) when Janelle Monae’s Dirty Computer tour reached the Hollywood Bowl. What was a cute “couples night” turned into an internalized disaster as I felt too “in the way” by my height, too encroaching with my gender. Projecting that “I’m ruining this for someone, someone this is more ‘for,’” marred a night with a loved artist for my beloved and me.

Staring at myself, I strained to hear, to understand. The aerobic instructor screamed while Prince blared. How I look, the parts too big and too visible, the gym attire too drab and jock, is painfully inescapable. I can’t ignore how broken I am. The misunderstood, misheard, foreign movements, a base incomprehension of the prompts (that seemingly I alone struggle to follow), hampered by my knee (torturously tender since high school), is an objective humiliation in the dance class mirror. There’s no eyes-closed grooving or “doing my own thing,” no interpretation, just screaming and speed. In a fastidiously inclusive, post modern, body positive space, I felt less than less of myself. While I’m not “othered” or unwelcomed—“too welcomed” if anything—it’s a poor fit, not 100% “for me.” My smiling expression couldn’t hide the distress flashing past my eyes for an hour. “Never again” I said to myself (and later echoed out loud to Mel, who invited me).

I don’t see myself when I Just Dance. Not even in between songs or as I leave my “dance space,” in the brief reflection of my TV’s dormant blackness. The game tells me the moves and measures, with an appreciated degree of technological fallibility in the attempt at fidelity. Any modifications to accommodate ailments—like not falling to the ground and crawling on my knees—are instinctively accommodated. Any dissonance between my body, the game’s directions, my avatar executing those movements expertly and my final score, is negotiated in real time, for me and by me. Any embarrassment is nonsensical. There’s no one around to watch, no one to know, no one to judge or for me to project judgment onto. It’s just me, Mel, and sometimes a family member. Sandee, our dog, watches from her cage, avoiding our rapidly moving and chaotic footwork.

The world of Just Dance isn’t “me” and playing the game isn’t a gateway to “get away.” I’m not flying to a fantasy land. Just Dance isn’t a miracle panacea for any and every discomfort or anxiety. It's a game, a tool with quirks and limitations. It didn’t replace going out to a dank den with slippery floors and scintillating spirits, getting full on “Memphis Soul Stew.” It’s just “a different thing.”

My brain is wired for spotentity; I loosen my grip once I get a handle on things I enjoy. The “novelty to proficiency to apathy” pipeline has laid waste to many hobbies. I don’t know if or when I’ll lose all interest, or what will keep me tethered to any passing obsession.

I just know I “know know” Just Dance. Its dimensions are formally set in relation to my own boundaries. I know what it is and what it is to me. At least I can take comfort that the fixation diminished in returns never felt too far away to turn to. Just Dance, while “known,” still has true joy, expert craft, clockwork curiosity, and some resilient, dependable feedback loops. Can’t say that for everything. Can’t say that for most.

Just Dance 2023 Edition promises to advance the franchise. It looks different, fresher, and has a UI like a music streaming service. Developers have expanded story modes and community events, with plans to update content throughout the year in “seasons.” Synchronized online multiplayer debuts this year, (just as people are more likely to meet up with friends in person). My purchase will be more about inertia than revelry, like my brother who’d buy a new console at launch only to play two sports franchises, NBA2K and Madden, and their annual releases. I used to laugh at that practice, but I get it now. No matter how new, deep and rich the franchise gets, my relationship to Just Dance remains as surface and base as “I like dancing. I like Just Dance.”

Of the many Just Dance related songs that always juice me up, that always makes me smile in a fleeting memory, that I find myself singing around the house, that I don’t think about or think I’ll play until hearing its preview and succumbing to its irrefutable, dependable delight, “All You Got to Do (Is Just Dance)” takes top honors. "All You Got to Do"

"All You Got to Do"

Literally “the most” Just Dance song, “All You Got to Do,” an original composition for the series penned by Tom Salta and performed with Oktavian and Missi Hale, debuted as the theme song to Just Dance 2018. Pulsing and bubbly, the track bounces and flourishes on solid Pop craftsmanship. Its lyrics, and corresponding Just Dance stage, is rich with cosmic imagery and collectivism, where all listeners and dancers are told they can embody “neon dynamite” and that they might “break the speed of light,” if only they just dance. The choreography is easy to follow and easy on the body. Groovy rays connect realms and incorporate other characters from the Just Dance universe, circling the song’s Memphis Design clad coach as they gesticulate to the sky, to the ground, and all around.

While cheesy, repetitive and saccharine, “All You Got to Do” isn’t a command, it’s an invitation. As illustrated in one of Just Dance’s crowning achievements, during the song’s bridge, the music, choreography, visuals, and interactivity coalesces in serene sentiment:

“And when the world has got you down

All you do is dance

I promise we can break right through the clouds

All you do, all you do is dance”

Two-stepping, arms out like a bird in flight, then hands raised and waving like tickling the sky, in that moment, for all time, in all ages, life couldn’t be more.