CONFRONTING NOSTALGIA WITH MAJORA’S MASK

Posted April 13, 2021

by Brandon Garner

Whenever a friend of mine says that they’re thinking of re-playing an old game, I always ask the same question: “How does it hold up?” This hindsight is the unfortunate side of the coin of rapidly evolving world-consciousness. An upsetting number of works of art that seemed incredible at the time now just come off as too in-the-moment when seen through a rearview mirror, largely because we’ve accelerated our cultural understanding of definable craft in such a way that we now learn how to make those things better than ever before. Movies and video games that were constantly pushing the envelope in the past have been left in the dust because they now seem like slow prototypes when viewed from our futuristic lens. American Pie is a prototype for Superbad, the Goldeneye game is a prototype for Call of Duty. While we’re talking about this, let me warn you: don’t re-watch Mystery Men. Let it stay in the past where it belongs, along with Secret of Mana and that one voice recorder from Home Alone 2.

Such a burden of living in our time (yes, burden) is why it is such an absolute joy to revisit a relic and find that your younger self was actually right to proclaim its brilliance. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask has stayed in my past for a very long time because I feared my younger self was wrong. Originally released as a sequel to the groundbreaking monolith that was Ocarina of Time on the Nintendo 64, it had a monumental task of standing up against a game that is still mentioned today in hushed tones for the standards it set in video game 3D world design, combat mechanics, puzzles, and immersion. How could anything reach such tall shoulders and then proceed to stand upon them?

Majora answered this question with an answer only an insane genius could think of: don’t stand on the giant’s shoulders, get gravity boots and stand sideways on its belt-buckle. The story of Ocarina was such an epic tale that it needed to utilize a timeskip, and to have a direct sequel to that story would only result in attempts at living in old glory, much like Uncle Rico in Napoleon Dynamite (mostly holds up, btw). MM fixes this issue by having Link explore a completely different region, which is plagued by the threat of an extremely minor character from the previous game. Instead of being a narrative sequel, this is more of a narrative expansion, much in the same way Chrono Cross was to Chrono Trigger, revealing more of how the world works when it comes into direct contact with the protagonist. Everybody wins: references to the previous experience are still valuable, but there’s no longer a crushing weight of meeting the original story’s structure and expectations. And when you free yourself of that weight, you can really let your imagination run wild.

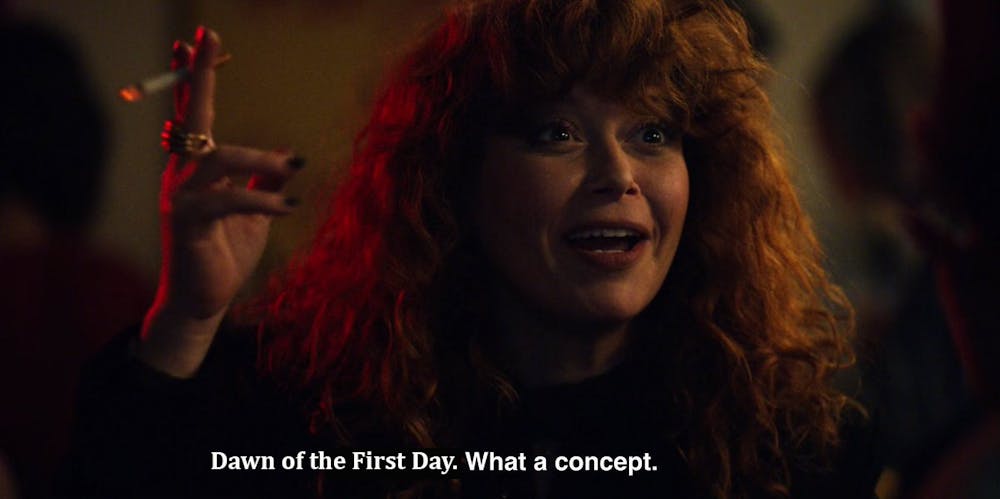

Majora made choices that seemed downright outrageous at the time: instead of tackling a massively long single quest, the game is relatively short but takes place in a world filled out with a striking volume of optional tasks. Instead of adding new tools, you’re able to change the main character’s entire appearance and function whenever you want. And the most surprising change of all: you don’t experience events over linear time the way normal human beings do, you idiot, you instead live in a Groundhog Day scenario. Yes, this is a Groundhog Day Zelda. Feel free to picture Bill Murray with a green hat and sword here, and you’ve pretty much got it. And while that may sound incredible when you read this in the year of our Lord 2021, it was an extremely controversial move at the time of release. If you weren’t playing Zelda games back in the turn of the millennium, you missed out on some real debates on the playground. A lot of people didn’t like the new takes. What were these… these side quests? Those don’t belong in a game, just give me a long main thing to do! And don’t get me started on the arguments on quantum mechanics we had after our seventh grade science class! Because there were none. We were dumb children.

I personally loved the game when it came out. I enjoyed the adventurous changes, and generally had a great time. Not to mention my aunt thought I was going to hell for playing the game, because she was Christian and the game had… masks, I guess? Either way, this made the experience absolutely rule. But as I mentioned, a lot of people didn’t enjoy the game when it came out, and additionally, young me liked a lot of things that I’m not terribly proud of now. (I say this as I shamefully close a tab I have open of the 1996 Sonic the Hedgehog anime movie - afraid to see if it holds up.) Majora’s Mask was re-released a few years ago with a host of quality-of-life changes on the 3DS, but I was too scared to try it. What if my enjoyment of the game would be erased by finding that the experience was too of-the-moment? What if the kids who didn’t like the game were right? What if young-me was, similar to present-me, a giant dummy? There were a lot of fears keeping my replay at bay, but I’ve found myself referencing the game so often lately that I decided to finally get down to it. And boy was it a complete delight.

Not only were the naysayers complete FOOLS, young-me was wrong for not liking it enough. Majora makes so many choices that are awe-inspiring to me even now. Taking the “expansion sequel” direction is already a great decision, but then the game says “hold my beer” and takes even bigger risks that pay off big time. The story has a much darker tone - instead of starting in the Chosen One’s childhood home, the tale begins with Link trying to find Navi, his closest friend who has abandoned him. He then runs into the barely-remembered Skull Kid, who now has been corrupted by an extremely spooky mask to become a complete dick. After pushing Link around with two companion fairies, who have thug-like “get him, boss!” attitudes, the Skull Kid turns Link into a deku scrub through an extremely visceral visual experience. Link then heads into Terminus, a new world where the Kid decides to personally screw with every inhabitant’s life before giving the moon a scary face and hurling it towards the town. You only have a measly three days to stop said moon, so the obvious solution is to reverse time to the beginning of that three-day mark whenever it suits you.

You know, three-day-rewinding? That idea is weird, but it works by making the moment-to-moment experience much more palatable. Cutscenes no longer rely on waiting for these blocky, old characters to fully animate, as with all other games - they instead have the animations jump around like a cartoon, creating livelier moments. When I originally saw this as a kid, I was a little surprised that it was happening. But as an adult? I want to ask why most games aren’t doing this now. It’s such a simple technique that borrows from animation, and it WORKS. Dear Next Final Fantasy: please stop thinking your animations are good. Just use conventions like this and save yourself a headache. Then on top of that, there are intentional cinematography choices. Instead of relying on the old standby of “person A talk, person B talk, tilt the camera to sky and zoom,” we have shots where the camera keeps focusing on the listener in a conversation, and it just keeps focusing and focusing, allowing the listener to really convey the impact of what’s being said. More mature choices like this, please!

One element of moment-to-moment experience is the topic of game mechanics, but Ocarina already had a robust system, so Majora just took that and dialed it up to 11. Most of your jumps across chasms are now backflips or mid-air cartwheels (HOLDS UP, BABY). Your fairy companion this time around has an actual personality instead of being an expositional robot. There’s now a more populated open field, teeming with life. There are character transformations that completely change your rhythm of movement, ranging from a Deku scrub to a Goron and a Zora. Each radically shifts your flow: the scrub launches into the air and glides, the Goron turns into a Mad Max-esque car wheel with spikes on it (is this why my aunt thought I was going to hell?), and the Zora torpedoes through the sea. My head exploded at the metal-as-hell vibe of those spikes the first time I saw them as a kid, and now my head still explodes, but at the way it fits in the world. Becoming a spiked racing wheel is weird, but Zelda is a weird franchise. It consists of rocks that give you advice and maniacally-laughing giant fairies. Lean into the weird!

An experience that takes this many swings is bound to have some misses, which in this case are the infamous time system and the mediocre dungeons. While they aren’t terrible, the dungeons also aren’t anything to write home about. I don’t have childhood memories of them, and that’s for a reason, barring the one in the Canyon region. This final dungeon requires a masterful use of every ability you’ve received in the game and then has you do it some more, but upside down. It’s excellent, but it doesn’t right the wrongs of its sibling experiences. And while completing these labyrinths and your many side quests, you are given three day sprints to do so, but you’re reminded of this time limit for every moment of your waking existence. Having a schedule makes sense in theory: every character within the world has their own schedule each day, and a real-time second moves for each in-game minute. But you’re forced to watch this time tick by on a clock at the bottom of the screen, and all mid-task progress will get reset to zero when resetting the time period. This recipe makes it incredibly easy to focus way too much on the clock and try to cram as many tasks as possible into each three day period, and I’m getting stressed just typing that out. This could have been rectified by just making the schedule appear in your notebook instead of shoving it in your face at all times, but here we are. In effect, the game becomes a mental health exercise of making yourself ok with deadlines by not giving yourself too many to work with at a time. Maybe this was actually a genius move to make you a healthier person?

The real homerun with this game, however, is the absolutely insane story - a kid with “skull” in his name is now even scarier than his already terrifying name, he turns you into a wood creature thing, and then hits a town with a moon. How could such a weird premise be not just playable, but believable? The same as every good story: the characters. The characters are all alternate reality versions of those found in Ocarina, with the same personalities but now with more history. Some of these people are in hilarious positions when compared with their previous roles, such as a former dungeon boss now giving boat tours through a swamp. The inhabitants of this world have full, developed lives that you can impact, and you’re motivated to do it so that you can receive masks from the citizens which help you do various tasks such as seeing invisible ninjas, sprinting quickly, or just straight-up dancing (holds up even more). Even the villain is quickly revealed to have a heartbreaking reason to be who he is, and you can help him too. And therein lies the coup de grâce: the dark tone doesn’t just exist for a power fantasy or adolescent tendencies - it exists because the world IS a terrible place unless you do everything you can to make it better. And you CAN make it better. Even writing that sentence now hits me where I feel it.

And look, is it perfect? No. But Majora’s Mask is old enough to be your drinking buddy, and none of them are perfect either. Its one major failing (we’re looking at you, time resets) isn’t nearly enough to warrant skipping it. The story and characters alone are worth the jaunt, but then you have a system that only improves on one of the greatest games of all time, making it stand the test of time even better than said original.

You should play it again. It holds up.